- Your cart is empty

- Continue Shopping

India: The True Motherland of Achar.

When we speak of achar, we often talk about taste—fiery mango, tangy lemon, spiced garlic. But achar is much more than food. It is a window into India’s ancient ingenuity, a practice that links the Indus Valley with modern kitchens, a bridge from Ayurveda to today’s jars of Videgha. For centuries, many histories have credited Mesopotamia with the “first pickle.” Yet if we look closely at India’s own timeline, the evidence suggests something even more compelling: India is the true motherland of achar, home to the oldest continuous tradition of pickle-making in the world.

The Civilization That Knew Its Spices.

The Indus Valley Civilization (IVC), flourishing from 3300–1300 BCE, is among the oldest urban cultures alongside Mesopotamia and Egypt. Archaeologists have unearthed storage jars, grains, oil-seeds, and spice residues from sites like Harappa and Mohenjo-Daro. Mustard seeds, turmeric, and salt—three pillars of Indian achar—were already staples of daily life.

While Mesopotamia left behind clay tablets describing cucumbers in brine, the Indus Valley script remains undeciphered. This makes it unfair to claim that India lacked pickle-making knowledge. The absence of a readable recipe is not the absence of practice. Given India’s abundance of spices, oils, and sunlight, it is entirely logical to believe that our ancestors were already fermenting and preserving foods thousands of years ago.

Ayurveda: Science Meets Fermentation.

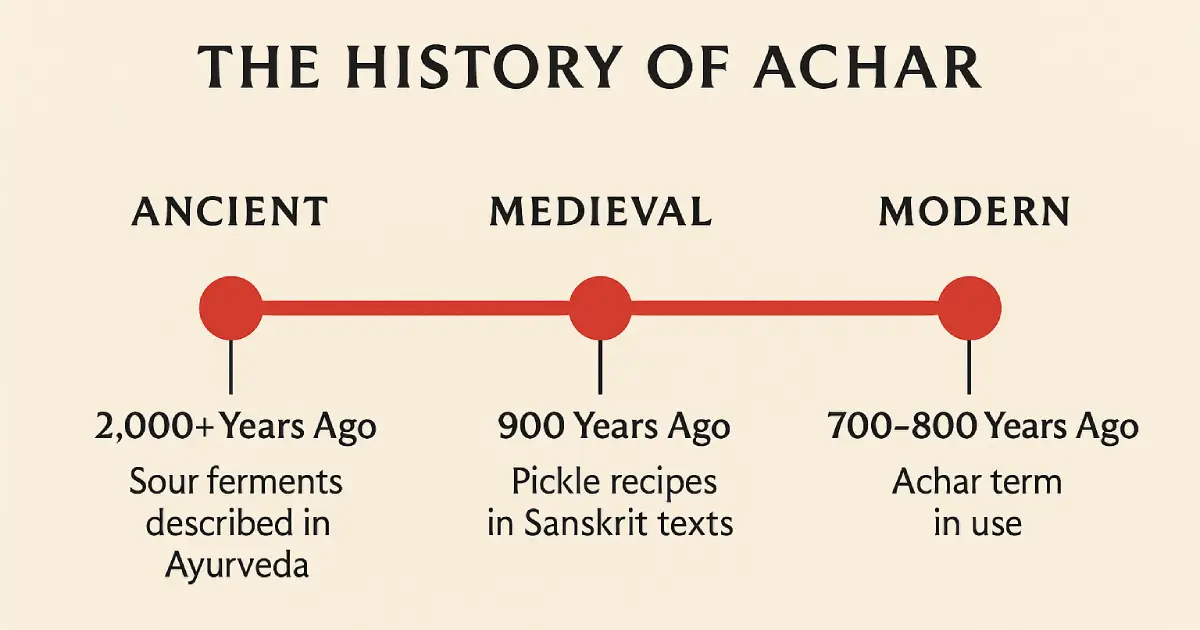

By the time we enter the age of Sanskrit texts, the evidence becomes unambiguous. The Charaka Saṃhitā and Suśruta Saṃhitā (600 BCE–200 CE) mention sour ferments such as śukta, kanjika, and dhānyāmla. These weren’t simply condiments—they were prescribed for digestion, balance, and immunity.

Ayurveda created an entire category known as Śukta Kalpanā, which detailed sour, acidic preparations resembling early pickles. Here, the practice of preservation was not just culinary improvisation but codified science. While Mesopotamia noted cucumbers in brine, India systematically studied the effects of preservation on the human body.

That makes India unique: it was not only making pickle-like ferments but also understanding them scientifically.

From Medicine to Menu.

Fast forward to the 12th century CE, and we see pickle-making celebrated outside of medical texts. The royal encyclopedia Mānasollāsa, written by King Someśvara III, lists pickles made of mango, lemon, ginger, and myrobalan (harītakī). These are explicitly food items, not medicine. This book is essentially India’s first “cookbook,” and it confirms that achar had become central to the royal palate by the medieval period.

From there, every region of India developed its own achar culture—Punjabi lime pickle, Gujarati sweet mango pickle, Andhra gongura pickle, Mithila’s sun-aged mango achar. The methods were as diverse as the land itself, but the principles—salt, spice, sun, and patience—remained constant.

The Word Achar Arrives.

Some argue that since the very word achar is borrowed from Persian, the practice must have been imported. But words and practices don’t always share the same birthday. The jars long predated the name. When Persianate culture entered India during the Delhi Sultanate and Mughal era, many Indian foods acquired Persian labels. Yet the techniques—sun-drying, oil-curing, spice-layering—are deeply Indian.

This means achar as a practice is older than the word achar itself. The Persian language gave a label to something India had already been perfecting for centuries.

Why India, Not Mesopotamia?

Histories often cite Mesopotamia (c. 2400 BCE) as the birthplace of the pickle because clay tablets mention cucumbers in brine. But if we take a wider view, India’s claim is stronger for several reasons:

- Civilization Age: The Indus Valley Civilization is older than Mesopotamia. Both had agriculture, trade, and storage technologies, but India had spices and oil-seeds suited to preservation in ways Mesopotamia did not.

- Material Evidence: Mustard seeds and turmeric from Indus Valley sites prove that the foundations of achar—oil, spice, salt—were already present.

- Textual Depth: Ayurveda systematically described fermentation and preservation techniques as early as 600 BCE. Mesopotamia never built a comparable knowledge system around pickling.

- Continuity: India has an unbroken chain from Indus Valley Civilization → Ayurveda → medieval cookbooks → modern household practice. No other region can show such continuity.

Thus, while Mesopotamia may have given us the earliest written “pickle note,” India gave the world the oldest living tradition of pickling—a tradition that continues, unbroken, in every Indian kitchen today.

Achar as India’s Living Heritage.

Unlike in the West, where pickles became standardized industrial products, Indian achar retained its soul. Every household has its own recipe, often handed down like an heirloom. In Mithila, achar is made through slow sun-aging, allowing spices and oil to mingle naturally, creating flavors that grow richer with time.

At Videgha, we honor this exact lineage. We do not rely on shortcuts or chemicals but on the same methods used by our ancestors—sun, spice, patience, and purity. Each jar is part of an ancient continuum that stretches back over 2,000 years.

To call Mesopotamia the home of the first pickle is to confuse written records with living practice. India may not have left cuneiform notes, but it left something far more powerful: a tradition that is alive, evolving, and deeply embedded in daily life.

When you taste achar in India, you are tasting not just spice and tang but the oldest continuous pickle-making heritage in the world. From the Indus Valley’s jars to Ayurveda’s sour ferments, from royal kitchens to Videgha today, India’s achar is not only food—it is civilization in a jar.

Read This Now – The Difference Between Homemade Achar & Mass-Market Pickles

1 Comment